据伍德麦肯兹1月24日报道,伍德麦肯兹《能源转型基本展望》认为,到本世纪中叶,全球气温将比工业化前高出2.5-2.7℃。为了将升温限制在1.5℃以内,符合《巴黎协定》,能源转型必须加速。

因此,能源转型必须加速。世界有这样做的手段、动机和机会。

加快能源转型将带来回报,无论是在经济方面还是在保护地球方面。但这将需要时间。分析表明,大部分持久的经济效益将在2050年之后实现。

通过避免气温上升造成的损害,防止气候进一步极端变暖可能会在未来三十年产生积极的经济影响,但实现这一目标所需的行动可能会产生抵消性的负面影响。根据对气候破坏和减缓全球变暖影响的现有经济研究回顾,估计将变暖保持在1.5°C以内将使2050年国内生产总值(GDP)预测减少2.0%。

随着时间的推移,新的过渡技术,即电动汽车、公用事业规模的电池、氢气和碳捕获与封存价格逐渐下降,低碳投资将比逐步淘汰的高碳替代品更具竞争力。这一转折点将在2035年左右出现,此后全球GDP增长将超过当前基本假设,这意味着损失的经济产出可以在本世纪末得到补偿。

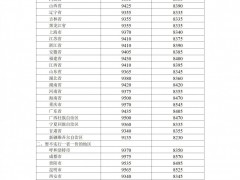

一些经济体将比其他经济体感受到更多的影响。碳氢化合物出口和碳密集型经济体的经济可能受到最大的冲击。欠发达和低收入经济体将承担不成比例的高负担。对低收入国家的气候融资,包括政府转移支付和私营部门投资,可以帮助解决不平等问题。但是,真正公平和公正的过渡将需要超越目前期望的行动。

已经接近净零目标的经济体从现在到2050年将看到较小的经济影响。对于少数幸运的经济体来说,转型根本不需要造成经济损失。那些处于更有利地位的国家,通常是较富裕的经济体,有很强的投资新技术的倾向,甚至可能在2050年之前在经济上受益。

一些面临1.5°C目标要求而负担最大成本的国家也是预计在未来30年内,人口增长最快的国家。对人口的影响是气候变化的众多不确定因素之一。如果限制全球变暖能够提高人口增长率(按人均GDP计算),那么脱碳的成本可能会更大。

王佳晶 摘译自 伍德麦肯兹

原文如下:

No pain, no gain

The economic consequences of accelerating the energy transition Wood Mackenzie's base-case Energy Transition Outlook sees global temperatures 2.5-2.7 °C above pre-industrial levels by mid-century. To limit this warming to 1.5 °C, in line with the Paris.

Agreement, the energy transition must accelerate. The world has the means, motive and opportunity to do so.

An accelerated energy transition will pay off - both in economic and planetary terms. But it's going to take time. Our analysis suggests that much of the lasting economic benefits will materialise beyond our forecast horizon of 2050.

Preventing more extreme warming is likely to have a positive economic impact over the next three decades, by avoiding damage caused by rising temperatures, But the actions required to deliver it could have an offsetting negative effect. based on a review of existing economic studies on climate damage and the impact of mitigating global warming, we estimate that keeping warming to 1.5 °C would shave 2.0% off our base-case gross domestic product (GDP) forecast for 2050.

As new transition technologies – electric vehicles, utility-scale batteries, hydrogen and carbon capture and storage - come down in price over time, there will come a point when low-carbon investments are more competitive than phased-out high-carbon alternatives. We think the turning point will be around 2035, after which global GDP growth will outpace our base case, meaning lost economic output could be recouped by the end of the century.

Some economies will feel the effects more than others. Hydrocarbon-exporting and carbon intensive economies are likely to see the biggest hits to economic output. Less developed and low-income economies will bear a disproportionally high burden. Climate finance for lower-income countries, including government transfers and private sector investment, can help address inequity. But a truly fair and just transition will require actions to exceed our current expectations.

Economies that are already closer to net-zero targets will see a smaller economic impact from now to 2050. For a fortunate few, the transition need not result in economic loss at all. Those that are better positioned - typically wealthier economies with a strong propensity to invest in new technologies - may even benefit economically by 2050.

Some countries facing the greatest burden from the costs of a 1.5 °C pathway are also among those expected to see the fastest growth in population over the next 30 years. The effect on population is one of the many uncertainties of climate change. If limiting global warming lifts population growth, in per capita GDP terms, the cost of decarbonisation could be even greater.

免责声明:本网转载自其它媒体的文章,目的在于弘扬石化精神,传递更多石化信息,并不代表本网赞同其观点和对其真实性负责,在此我们谨向原作者和原媒体致以敬意。如果您认为本站文章侵犯了您的版权,请与我们联系,我们将第一时间删除。